We've already blogged George Osborne's latest tax speech, and our disappointment that he's still not prepared to offer a bankable pledge on cutting Labour tax'n'spend (see here). As far as we can see, there's no meaningful difference from what Darling set out in October.

Corin Taylor has already picked him up on one point he made, which was that cutting spending growth below Labour's planned 2.1% pa would be to "head off onto the margins of the political debate," chasing a target that "would be lower than anything Margaret Thatcher achieved during the economic turbulence she faced in her first parliament".

Corin sets out the history of real public spending growth for the last 35 years so we can see the whole picture. He argues that although spending did indeed grow by more than 2.1% pa during Thatcher's first parliament (2.3% pa to be precise), it was an extraordinarily turbulent time. Over her whole period in office she got spending growth down to 1.5% pa, even taking account of the higher growth in the early years. He asks:

"Now, is it really correct to say that 2.1 per cent per annum spending growth is tighter than under Thatcher?"

We've taken a closer look at that turbulence during Thatcher's first parliament, asking how much of Thatcher's 2.3% spending growth was actually down to a weak economy, and its impact on welfare and other cyclical spending? After all, the Darling/Osborne plan is stated on a cyclically adjusted basis- ie if growth turns out lower than assumed, spending will be allowed to flex upwards from his planned 2.1% pa. Comparisons are only meaningful if we look at Thatcher's record on the same basis.

From 1979 Q2 to 1983 Q2, as Thatcher wrestled that horrific hangover from the dismal seventies, real GDP shrank by nearly 1%. Yes, that's right, over the whole four year period the economy got smaller (see here).

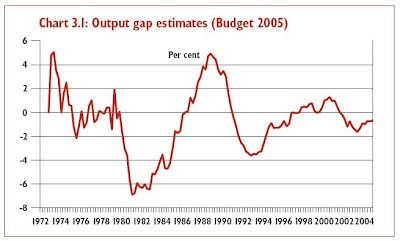

But according to HM Treasury, trend GDP growth at the time was 2% pa. So as actual GDP fell, there opened up a huge gap between that and potential trend GDP. In fact, by the end of Thatcher's first term the Treasury reckons this output gap was between 6 and 7 per cent:

Just let that sink in. A 6-7% output gap means that GDP is massively below its full-employment level. In today's terms it would be equivalent to us losing around £100bn pa from our national income, or £4,000 per household. That is serious turbulence.

Just let that sink in. A 6-7% output gap means that GDP is massively below its full-employment level. In today's terms it would be equivalent to us losing around £100bn pa from our national income, or £4,000 per household. That is serious turbulence.

And obviously it put serious upward pressure on government spending. But how much?

Luckily for us, adjusting public finances for the cycle has become a major state industry under Gordon Brown, so we can turn to the Treasury's own ready reckoner.

The key Treasury paper was written by Ed Balls when he was still at HMT, and has been used ever since as the basis on which they cyclically adjust the public finances for Golden Rule purposes. It says:

"a 1 per cent increase in output relative to trend is estimated after two years to reduce the ratios of Total Managed Expenditure and Public Sector Current Expenditure to GDP by about ½ percentage point"

Flipping that round for the Thatcher experience, a 1 per cent shortfall in output relative to trend is estimated after two years to increase the ratio of public spending to GDP by about ½ percentage point.

Which means that Thatcher's spending total in 1982, with GDP 6-7% below trend, needs to be cyclically adjusted (downwards) by an amount equivalent to 3 - 3.5% of GDP.

Now that gives us a very different picture of spending restraint in Thatcher's first term. In 1982-83, Total Managed Expenditure (TME) was running at 48.7% of GDP. Cyclically adjusting that by 3% or so reduces it to 45.5%. Translated into spending, that's a cut of over 6% in the unadjusted total.

When she came to power in 1979, HMT's figures suggest the UK economy was roughly on its longterm GDP growth trend (see chart above). So we need to credit her with the whole of that 6%. In other words, whereas her first term saw unadjusted public expenditure grow by 2.3% pa, or a total 9.5% over the four years, cyclically adjusted that falls to about 3% overall, or about 0.8% pa.

When George Osborne talks about his proposed 2.1% pa public spending growth being as tough or even tougher than Thatcher, he's totally disregarding this entire cyclical effect. Cyclically adjusted, Thatcher's first parliament held spending growth to well under 1% pa.

Yes, it was politically difficult, but she and her ministers did it. And they laid the foundations for the prosperity we've been living off ever since.

What does this mean for the current debate?

Well, the Darling/Osborne spending plan assumes GDP growth of 2.5% pa pretty well into the indefinite future. But what if it doesn't materialise? What if we get whacked by another bout of eighties-style hangover? What if say we don't get any growth for the next four years?

Four years of zero growth would leave us 10% below the Darling/Osborne GDP assumption, and public spending growth would balloon. We could forget 2.1% pa - using that same HMT ready reckoner, on current plans, public spending in real terms would grow by well over 5% pa.

Within one parliament we'd be right back up to government spending around 47 - 48% of our GDP.

Osborne talks about heading off into the margins of political debate, but he should at least recognise that Thatcher's first administration was far tougher on public spending than he plans to be.

He should also think about how he'd handle four years of minimal growth locked into Darling's spending plans. How exactly would he stop public expenditure crushing the economy just as it did in the low growth seventies? We can see how Thatcher did it: what's his plan?