The reality is that hardly any of us believe all those government claims that crime is plummeting, or even this year's more measured assurance that "crime is stable". And in truth you get the distinct impression that the Commissars don't believe it either- why else would they choose to sneak out the report under cover of that headline grabbing inhalation smokescreen?

So what do the latest numbers really say? I've taken a canter through the 200 page HO report to find out.

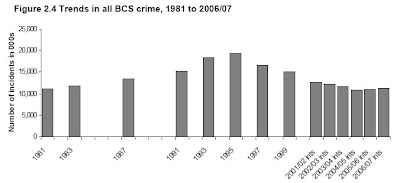

Here's their headline summary chart, showing crime as measured by the British Crime Survey. The BCS is the government's preferred measure of crime, although as we've discussed before, it is actually little more than an elaborate opinion survey. But it does show a dramatic fall in victims' experience of crime since its peak in the mid 1990s:

There are a couple of immediate points to note.

First, thank goodness for Michael Howard. If he hadn't insisted on pushing through his prison building programme- despite everything the BBC and their multi-million presenter Jeremy Paxman could throw at him- we'd have had a disaster on our hands. Note how as soon as the present government took over and the building programme fizzled out, the BCS crime fall also came to an end. Indeed, BCS crime has actually increased for the last two years running (we can simply guffaw at Tony McNulty's gloss that the increases are "not statistically significant"- it's up 4% in two years).

Second, we should all understand that the BCS concept of "crimes" includes a ragbag of trivial items most of us don't lose a second's sleep over. No surprise that less than half of BCS crimes end up getting recorded by the police, and for some- like perceived violence without any injury- the proportion recorded is more like 10%. If crimes are that trivial, why would we care? Are they even real crimes?

What we really want to know about are the serious crimes. Those are the ones the key stats should home in on.

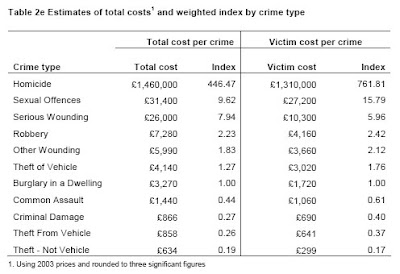

Fortunately, the Home Office spells out what it thinks they are. Its report provides this table of the estimated economic costs of different crimes. And it includes the costs to us, the victims:

Rational economic beings that we are, it's pretty clear which crimes we take most seriously- homicide, sexual offences, serious wounding, and robbery. And rational number crunchers that we are, we'd much rather take the number of recorded crimes from the police, rather than some opinion poll where someone reckons they were the victim of of a serious wounding but never bothered to report it.

Let's consider the period since 1997 (see Report table 2.04). Since then, the recorded crime category of "most serious violence against the person" (including homicide and serious wounding) was up 35%. The category "most serious sexual crime" was up 40%. And robbery was up a staggering 61%*.

A straight average of these three categories says that serious crime- the crime we actually worry most about- is up by 45%.

Serious crime up 45% since Labour took over.

So when Home Secretary Jacqui Smith tells us straightfaced "today's crime statistics show we are holding the improvements to the falls in crime", she must be figuring we're as fond of the old Wacky Baccy as she once was.

Of course, the government and its apologists argue that you can't use police recorded crime data, because the coverage and counting method has gone through two significant changes since 1997.

How very convenient that is.

But the truth is the changes primarily affected less serious crimes, with for example the inclusion of a raft of additional summary offences in 1998. And by focusing on serious crimes, we avoid most of that noise*.

Whatever the government may say about the crime wave being all in our minds, the serious crime we actually worry about has shot up since they came to power.

* Tedious stats footnote- The recorded crime stats have had two databreaks since 1997. The first was in 1998, but is not a problem because the Home Office published "before" and "after" stats, and in the case of our serious crimes there was virtually no difference. The second in 2002 is more of a problem because there are no before and after stats. But for our serious crime categories, the break doesn't look to have affected things that much- even if you exclude the entire increase between 2001-02 and 2002-03 (a pretty extreme assumption), our 45% increase figure only falls to around 30%- still a chunky increase.