How bad is all this going to get for UK taxpayers?

We've already taken on a huge stack of bank debt - provenance unknown - and now we're heading into the worst recession since the 30s. Public spending will soar and tax revenues will plummet, racking up public debt way beyond anything currently envisaged.

BOM readers will be familiar with HM Treasury's rule of thumb on the fiscal consequences of economic downturn. In brief it says that a 1 per cent decrease in output relative to trend is estimated after two years to increase public sector borrowing by just under ¾ percentage points of GDP.

So let's grit our teeth and see what that's likely to mean for borrowing over the next few years.

On GDP growth, here's what Mr Darling assumed in the March Budget (click on chart to enlarge):

So between 2008-09 and 2012-13 he assumed cumulative growth of 12.3%, or an average of 2.35% pa.

There isn't the remotest chance we'll now see anything like that. Last week the IMF slashed its UK growth forecast to 1% for this year, and a fall of 0.1% in 2009.

Even that now sounds optimistic, and it says nothing about what happens thereafter.

As we've blogged before, previous banking crises have left far bigger craters. The best case is something like the Swedish crisis in the early 90s, where the authorities managed to stabilise their busted banks with a massive equity injection (ie the Brown/Darling plan). But even that saw GDP falling by 6% in three years. And you won't need reminding what happened in 30s America - GDP fell by 30% in four years.

Right now, given that we aren't just dealing with a single economy, we should probably assume that that the Swedish experience is the best case. Ballpark, we might very easily see a GDP fall of 5-10% over say the next 3 years, followed by a very slow and very hesitant recovery.

Which means that by 2012-13 - the middle of the next Parliament - GDP could easily be 15-20% below the level projected by Darling in March.

What would that mean for the public finances? Applying HMT's rule, it means that by that point, on unchanged tax and spending policies, annual borrowing would be overshooting Darling's Budget forecast by 10-15% of GDP. Or in money terms, £150-200bn pa - a massive increase on the £23bn borrowing projected in March.

Ah well, you say, borrowing needs to be cyclically adjusted. As Keynes pointed out, governments have to borrow during periods of economic weakness, so why worry? It all comes right in the long-term... we'll pay it off... one day... when the lights go on again... kind of idea.

Hmm.

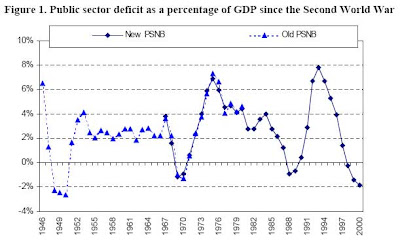

Borrowing on that scale is unprecedented in modern times - even in the dark days of the 1970s and the early 90s we borrowed well under 10% of GDP. Here's a chart from the Institute for Fiscal Studies showing the history:

You see, when you borrow too much you can easily crank up a fiscal doomsday machine. Each year's borrowing adds to you outstanding debt, which then adds to your debt service costs. And your higher debt service costs add to your borrowing. Which then adds to your debt service costs, and so on until something Really Bad happens.

In particular, what if international investors don't wish to oblige? What if - like the 1970s - they don't fancy lending to a banana republic with a busted nationalised banking system and a serious debt habit? What if they decide such a country's currency is doomed? What if they demand to see severe fiscal restraint (including big tax increases) before they'll lend a bean?

What then?

Financial market excess has delivered a serious global recession. Public spending excess means that it will be especially punishing for British taxpayers.