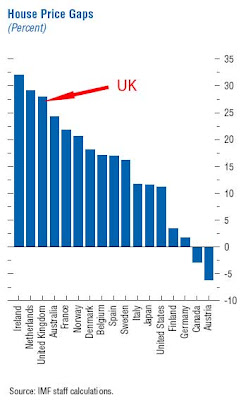

The IMF has caused quite a stir this week. Its latest economic and financial outlook papers ( here and here) have predicted that the credit crisis will cost $1 trillion, GDP growth will slow dramatically, and UK house prices may fall sharply. As its chart shows, UK house prices are the third most overvalued in the world (the "gap" being the difference between prices and what the IMF reckons is the value implied by underlying fundamental factors such as affordability).

But for taxpayers one of the most worrying headlines is that the IMF now favours publically funded bailouts of failing banks. That would be a seriously disappointing turnaround for an institution that has always been a bastion of monetary and fiscal rectitude. So we've taken a closer look to discover exactly what they do say.

Now, the trouble with IMF papers is that the really interesting bits tend to be written in IMFspeak. But stripped of technicalities, here's how the IMF spells it out, along with our verdict on each point:

1. Public policy should seek to safeguard financial stability and market functioning. Agreed

2. However, care should be taken to avoid creating adverse incentives or moral hazard that undermines discipline imposed on private players by such events. Agreed.

3. The public resources should be kept as small as possible. Agreed.

4. In a case of depleted capital, the preferred approach would be to take remedial measures and resolve [ie place in special publically managed liquidation] the institution if it is no longer viable. Shareholders should bear the brunt of the adjustment. Agreed.

5. When the failure of the institution poses a systemic threat, the case for public assistance may need to be considered, but only after shareholders have borne the full brunt, with clear mechanisms in place to ensure that operations continue on a commercial basis, and with an unambiguous plan for exit by the public sector. Agreed.

So the short version is busted banks should be liquidated (ie shareholders lose everything) and reconstructed/sold/run-off over a period of time by the authorities. Taxpayers should be last in the queue for contributions. With which we agree 100%.

The obvious next question is to ask how that all stacks up against how Mr Brown handled the Northern Rock crisis? Let's run through the IMF's guidelines.

Did he safeguard financial stability and market functioning? 6 months of nervous faffing around and the first High Street bank run in 150 years- hardly.

Has he created adverse incentives and moral hazard? Well, eventually, he did pull the plug, which is good. But against that, he spinelessly distanced himself from the tough stance taken by his own Bank Governor, undermining Mervyn King's authority in the process, which is very bad. The bigger banks will certainly guess they could win any future game of chicken with such a wuss.

Has he kept the public resources small? Hardly- we taxpayers are on the hook for £100bn secured only against the increasingly uncertain Crock loan book.

Have Crock shareholders born the full brunt? Yes, most of them have taken a loss, but Brown left the door open to compensation by undertaking to appoint an independent valuer (see this blog). And taxpayers are also at risk from that EU human rights shareholder compensation suit.

Does he have an unambigous exit plan? Don't make us laugh- as we blogged here, it's highly unlikely the Crock will ever be able to survive without its taxpayer guarantee. There is no exit plan, just a vague hope that something will turn up.

So that's... let me see... nought out of five.

Not very good.