So what should we make of the schools lottery fiasco? Brighton's attempt to impose Marxist-Leninist principles on school place allocation (originally blogged here) has backfired spectacularly, with an outright reduction in the proportion of kids getting their first choice secondary school. It's reportedly declined from 84% to 78%, so more than one-in-five kids won't get their top choice.

The first point to make is that this reflects a national crisis. The Guardian has surveyed local authorities and reports:

"Up to 120,000 of the 560,000 families expecting to receive an offer of a secondary school place in the post this morning will be disappointed as local authorities across the country report fewer pupils being offered their first choice of school.

Islington saw one of the biggest falls, with 59% getting their first preference - down nine percentage points from 68% last year. Barking saw a drop from 73.5% to 71.5%; Hammersmith from 62% to 60%; and Westminster from 69% to 66%." (See also the Times survey here).

Second, this is yet another example of our politicos promising the earth but not having the faintest clue what that might actually entail. Blair was constantly banging on about school choice, but as teachers union boss John Dunford says, the reality is quite different:

"Parents' expectations are wrongly being raised by the political rhetoric of parental choice when in fact all parents are able to expect is to express a preference of which school they attend."

Obviously Dunford has an axe - the teaching unions never wanted parental choice in the first place. But in highlighting the gulf between rhetoric and reality he points to the nub of the problem.

Far too much of this debate suggests choice is a consumer benefit. Parents can choose which school their kids should go to, just like they're able to choose which family car they'll drive. Whoopee!

But according to the polls, most parents don't want choice per se: hardly surprising, given how time consuming and stressful the whole nasty business can be (even when you're armed with a private school cheque book). What parents actually say they want is "good local schools". And that's the key point.

Choice is not something people necessarily enjoy exercising. But choice is a vital condition for driving progress. Unless people can actively choose between the good and the not so good, there's generally no way for society to work out which is which (leave it to the commissars to decide? you're not serious).

Of course, there is a key second condition for progress, which is real competition among suppliers. In the real world, that means when consumers in 1972 chose the Datsun Cherry over the Austin Allegro, there were consequences. The Japanese owned reliable car manufacturers thrived and expanded, and the shoddy British owned ones disappeared. But eventually the Japanese set up British manufacturing facilities and Britain's exports hit all-time highs. Kind of idea.

It's no good parents having the "right" to choose the good schools if there is no real competition among the schools and no consequences for them. All that happens is more and more parents have their choices over-ruled, and angst levels explode (sorry about that Tamsin- you've now been rejected by your first three choices, so Bash Street it is).

Imposing a lottery to allocate the good school places is both an act of desperate failure, and a block on future progress. There are no consequences for the poor schools because they get their places filled anyway. There is no driving incentive to improve. And next year we will be right back in the same place, with probably even fewer children getting their first choices.

At this point, somebody usually says "ah yes, but if you allow choice and competition among schools, you will create a lot of waste- school places aren't like water, you can't turn them on and off just like that, and underperforming schools would get left with loads of empty places we'd still have to pay for."

And there is some truth in that. Choice and competition is a messy, and in some respects wasteful, process. You do get pockets of oversupply developing alongside pockets of shortage. It all seems a bit random and chaotic.

The problem is, that's the only way we ever make progress. As Eric Beinhocker describes in his outstanding book The Origin of Wealth (see here), progress has always depended on large dollops of randomness and wasteful dead-ends.

But it also depends on something else. The randomness has to be contained in a structure that can somehow recognise and react to its results. Just having the randomness alone doesn't do it.

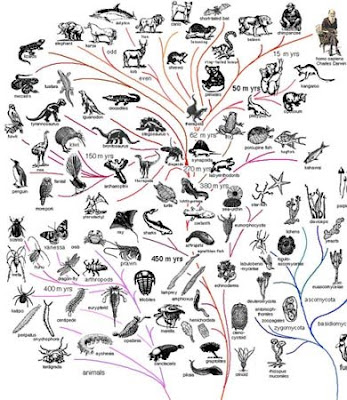

As Beinhocker highlights, evolution works through differentiation, selection, and amplification. That's how we made it out of the primordial soup in the first place, and that's how all our economic and material progress has come about ever since.

Which is why the latest economic thinking about how we get richer places heavy emphasis on evolutionary behavioural processes rather than intelligent design engineering processes. There is no grand masterplan, and systems that work on that basis are systems that are doomed to underperformance and ultimate extinction.

A school place lottery has the randomness all right. But it will do nothing whatsovever to improve Britain's schools.

Whatever their rhetoric may say, when it comes to schools, none of Britain's mainstream politicians has yet convinced us they're prepared to abandon their primitive faith in intelligent design.