Having already blown billions on bank bailouts, Mr Brown is now intending to blow even more by buying a bad bank.

At the risk of stating the obvious, let's just make sure we all understand what that means.

The Bad Bank will be owned by taxpayers and it will buy an unknown amount of so-called toxic assets from our commercial banks (and maybe some other financial institutions as well). In exchange it will hand over to the banks a huge amount of our cash and/or government-backed assets. In the trade, it's called trash for cash.

So why on earth would we agree to that?

Because, we're told, the commercial banks will thereby be cleansed of their toxic assets and can immediately get back to "Business-As-Usual". Which in this context means responsible lending to hard-working British families and successful British companies, rather than all that spivvy stuff they were actually doing before the music stopped.

Now, there's no doubt we need a banking system. And there's also no doubt that much of the existing one is effectively bust, propped up solely by taxpayers. But there are a number of obvious problems with this Bad Bank idea.

First, even if we do buy their toxic assets, how can we be sure the commercial banks will "get back" to all that socially responsible lending the commissars want? After all, we are falling into the deepest slump since the 30s, so left to themselves, banks might very well decide to keep all their nice new clean cash safe in say government gilts.

Most likely, the commissars will direct the banks in their lending, just like they're already directing the Northern Rock and RBS. The banks will have to meet targets for various types of loans, such as mortgages, and company credit facilities. But then, who gets them? And on what terms? And can I please have a lo-cost 50 year roll-up mortgage to buy my dream mansion home looking out over the sea in South Devon? It's the 1970s National Enterprise Board all over again, but scaled up by a factor of several billion (eg see this blog).

Second, what would we pay for these toxic assets? Bearing in mind there is no market price, who decides?

Clearly, the banks would want us to pay what they claim they're worth (or more). But half the reason nobody trusts the banks right now is precisely because they are almost certainly overstating what they claim is the value of these very assets. The banks' own estimate of prices is way too high.

But on the other hand, if we pay a realistically low price, the bankruptcy of the banks will be put up in lights - their capital will be wiped out at a stroke. Which would be highly embarrassing for all concerned - not least, Mr Brown himself.

In some smoke-free room, somehow, some way, someone's going to have square this circle. And with the Simple Shopper representing us against the bankers, taxpayers should be alarmed.

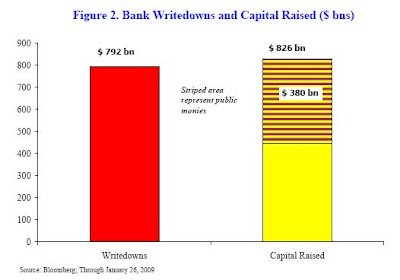

And understand this - even by Brown's standards, the sums at stake are enormous. According to the IMF's latest Global Financial Stability Report Market Update US and European banks have already been forced to write down their problem assets by $0.8 trillion, and the IMF estimates at least another $0.5 trillion to come by 2010. Indeed, it could be up to $2.2 trillion on US-sourced assets alone. And in ordinary everyday language, writedowns = certain losses.

As for how much toxic debt UK banks are holding, nobody really knows. Most estimates lie in the range £200bn - £400bn, but it could easily be more. And if the Shopper started buying it in on anything like standard Shopper terms you can bet it would turn out to be a lot more.

Cash for trash - taxpayers would get skinned alive.

Of course, there are those who reckon taxpayers shouldn't worry. The Times' Anatole Kaletsky is one, and on Monday - alongside nominating Mr Brown for the Nobel Prize in economics - he explained why. He told us we should take comfort from "five statistical facts... indisputable facts [that] are largely overlooked". So here they are, alongside our comfortless comments:

-

- "Taxpayers pay only if borrowers default on their loans... only the likely losses on these investments should count"... yes, true... but it's precisely those likely losses that the rest of us are so worried about.

- "Probable credit losses bear no relation to the current market prices of mortgages and other assets. Market prices are governed primarily by the liquidity of these assets, not by their default risk." We do have some sympathy with that point. But it's not really what we'd call a statistical fact. Our long and tragic experience is that you buck the market at your peril. It is of course perfectly possible that Kaletsky can somehow foresee that future defaults will be much less than the market is implying, but we seem to have encountered such seers before. And it's our money.

- "Banks can increase their lending to non-financial companies and households even if their capital continues to decline... 70 per cent of the growth in their lending has been to other financial institutions and this part of their balance sheet should now be aggressively reduced, leaving plenty of capital available for lending to non-financial borrowers." Unfortunately, one of the central problems is precisely that banks have become so entwined with these other financial institutions (hedge funds, sivs, etc etc) that they can't simply cut them off, without pulling the whole roof down on themselves. In other words, "aggressively reducing that part of their balance sheet" would precipitate further defaults that would smash the very capital base Kaletsky says would support all that lending to decent hardworking families etc. 70 per cent may be a statistical fact but it doesn't really help us here.

- "Even if additional bank capital must be injected, the pricing of this public support is unimportant, because the true returns to taxpayers will come not from capital gains in bank shares but from the vast additional revenues that will flow into Treasury coffers if economic activity can be revived." Well, yes, if we could somehow revive growth we'd all be better off. But why does that mean that taxpayers should be prepared to accept a shocking deal from bank shareholders?

- "Much of this investment could — and should — be financed by printing money at no cost to taxpayers at all... If more prudent bank liquidity management now results in a return of velocity of circulation to the levels in earlier decades, then central banks can and should print far more money to support economic growth — and the seigniorage profits from issuing this new money offers taxpayers huge gains." So printing money is a free lunch? Wonder why nobody thought of that earlier? True, re-imposing tough liquidity rules on banks (ie making them hold a substantial proportion of their assets in low yielding cash and near-cash) would effectively tax the banks to the benefit of taxpayers. But back in the days when we last had such liquidity ratios, we found it didn't mean government could just print vast new oceans of money. Or rather, when governments tried doing so, it ended in the great 70s inflation.

So for txpayers, there is no real comfort.

An alternative approach has been proposed by Prof Willem Buiter. His suggestion is that instead of the government setting up a Bad Bank, it should set up a Good Bank, fully owned and capitalised by taxpayers.

The Good Bank would take deposits, and would make loans to the kind of traditional straightforward borrowers mentioned above. And most importantly, it would give primacy to the protection of taxpayers. The Good Bank would:

"... acquire the deposits and the good assets of the bad banks or legacy banks. The good assets are, by definition, easy to value...

New lending business, indeed all new business activity would be undertaken only by the new good banks... No further guarantees should be extended to existing assets, either in the good banks or in the legacy bad banks... funding would be provided by the transfer of the deposits from the bad legacy banks, through loans from the state or through the sale of bonds by the new good banks to the state."

So Britain retains a functioning system of essential bread-and-butter banking, and taxpayers don't get ripped off. Sounds a much more compelling approach.

But a new bank fully owned by the state? It's not something we'd ever want to contemplate.

Until that is, we contemplate the alternative of bailing out the existing banks even more than we already have.

As we've blogged many times, taxpayers should not be bailing out bank shareholders. The Bad Bank proposal is a surefire recipe for stuffing us with a huge pile of overpriced busted debt. The risks and potential returns (if any) of that debt should stay with the shareholders who allowed their bank managements to acquire it in the first place.

Mr Brown should not be pledging more and more of our cash to support busted legacy banks. If the problems are that bad, it's time to think about how we can get some clean newco banks going to provide us with the plain vanilla banking services we need.

Taxpayers should not be forced to rescue the shareholders of failed banks, and apart from retail depositors, we shouldn't have to rescue their creditors either.