Yesterday's FT story on Corporation Tax got a deal of coverage. As you will recall, it said that one-third of Britain's 700 biggest companies pay no CT.

On the face of it, that's surprising because almost all of those companies will be making profits in the normal sense of the term.

Company taxation in the age of the multinational is fiendishly complex, and major governments are constantly battling to close down loopholes (eg stricter rules on transfer pricing and controlled foreign corporations).

But the principal reason profitable British companies pay no CT is that they can set off a multitude of tax allowances against earnings.

To start with, successive governments have established a raft of capital allowances, supposedly to boost investment in things they consider desirable. Closely related is Gordon Brown's R&D tax credit, which reduces the CT take by £0.6bn pa. And in that case, we know that at least half of it is pure bunce to the recipients- ie a windfall gain requiring no action on their part other than filling in the claim form (see here).

Then there is the issue of debt interest, which is an allowable expense. That means companies can reduce their CT liability by switching from equity to debt finance, as many have been doing. The Law of Unintended-But-Entirely-Predictable-Consequences highlights Brown's notorious abolition of ACT relief (the Great Pensions Grab) because that introduced the asymmetry in the first place (see this blog).

Thus have the Commissars ensured that complexity and unintended consequences are built into the very core of the system. No wonder that the true tax liability is often a "grey area" .

One curious aspect of all this is that the FT was reporting a National Audit Office report published six weeks ago. Quite why it resurfaced yesterday is unclear: presumably it got overlooked in the rush of reports issued at the end of "last term".

In any case, the report was essentially probing HMRC's capability in taxing big companies. And it did not paint a happy picture. In the face of rapidly mounting complexity and burgeoning multinationals who get the very best advice going:

-

- "The Department does not have a coordinated long-term strategy for staff continuity and recruitment of tax specialists into its large business work other than through internal transfer." (para 4.4). In contrast, faced with similar challenges, the US IRS has a programme to recruit 900 external specialists over the next 12 months

- "Large businesses considered that HMRC client relationship managers and tax specialists did not always possess sufficient knowledge of the industry." (para 4.7)

- "...they considered that the Department often failed to appreciate the practical issues and uncertainties surrounding international factors such as controlled foreign companies’ legislation, double taxation reliefs, transfer pricing and cross border-financing arrangements" (4.8)

The overall impression is of an organisation increasingly out of its depth- "staff ‘remain in their comfort zones, carrying out familiar tasks in familiar ways’ (2.38). They are bamboozled by the new challenges facing them.

So how much tax do they fail to collect? Amazingly, they have no idea. Whereas for other taxes, such as VAT, they estimate a "gap" against which they're shooting (16% in the case of VAT), they reckon it's too hard to do that for CT.

Others have been less reticent. The Tax Justice Network reckons it could be as much as 28%, or around £15bn this year.

So what to do?

It's pointless pining for a simpler world where companies stay still while governments help themselves to the till. Globalisation blows all that away.

It's also pretty pointless hoping we can somehow attract and retain enough one-step-ahead tax whizzos to work for HMRC: if they're that good, they'll follow the money down to the City, where they'll also escape working for the Commissars.

As we've argued before, the best and only realistic way forward is massive pruning of allowances and lower CT rates (see here for the Taxpayers' Alliance position).

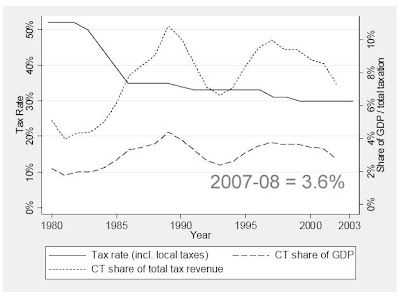

PS The chart above is taken from WHY HAS THE UK CORPORATION TAX RAISED SO MUCH REVENUE? by Devereux, Griffith, and Klemm (IFS 2004). It shows that reductions in the statutory CT rate have not cut CT revenue as a percentage of GDP. Part of the explanation is that allowances have also been reduced (ie the tax base has been expanded), but another driver is that overall profitability has also improved, supported of course by the cut in CT rates.